The Official Website of Don McGregor

The Official Website of Don McGregorI have often found that life as a Freelance Writer was filled with paradoxical extremes.

You could be exalted by finding a copy of one of your comics in a Glasgow, Scotland train station and realize how far the stories reached while wondering how you could retain your individual voice as a story- teller.

You could be at a Comic Convention and having people tell you with heart-felt, heart-TORN sincerity, what your stories mean to them, tears in their eyes bringing tears to your own eyes and yet not know where or when you will get to tell the next story.

Strangers will know you and care for you passionately, and you have never seen them before.

In 1978, I was invited to be the Guest of Honor at the London Comicon.

It was a time period that, for me, came to crystallize the paradoxical extremes of being a freelance writer. I don’t believe I realized this at the time everything was happening, but years later, in retrospect, this notion came to me as I kind of lived truth.

In 1977, I’d met Marsha Childers, and I was passionately in love with a beautiful woman in one of the most beautiful cities in the world. It would take us fifteen minutes to walk a city block; we couldn’t keep our hands off each other; her lips were warmth and desire; I didn’t want to be anywhere she wasn’t.

Conversely, it was also a transitional time as a creator. SABRE was due, sometime in the future, but who knew when since it was caught in unexpected struggles I had never foreseen. As late as March 1978, there were threats to turn Sabre white. I recently found my hand-written notes on my Marvel Comics Calender of that year. I’d forgotten the inter-racial aspect of Sabre was still going on at that late date and that the book was still being held in a ransom limbo, unless I agreed not to have Melissa Siren pregnant. What this meant, ultimately, is that with all the wonderful possibilities of life caught in Marsha’s voice and touch, there was the lingering wait for paying gigs to keep the writer alive.

When Colin Campbell first talked to me about attending the London Comicon I was reluctant. I didn’t want to leave Marsha, who was now pregnant. I just didn’t want to be without her. So, although I was honored that Colin thought enough of me to ask me to send me to the Con, I wouldn’t do it unless they could let Marsha come with me.

I wasn’t being arrogant or unthankful and I did not realize this was the first time an American comic book writer had been invited to be the Guest of Honor in England’s big annual comic convention. As my friend, Jane Aruns, once wrote to me: I saw so many women you could have been with, but you weren’t interested, until you met Marsha, and then you held nothing back.

Marsha was an unconventional woman. I was the comic book writer, and some people often thought of me as the wild one. But Marsha was often gutsier than me, and certainly wilder. I wasn’t even in her league. Paul Simon wrote the words in the song Kodachrome that the women he had known in his life couldn’t compete with his sweet imagination. Apparently, he had never been with a woman like Marsha. She was flesh and blood reality and she made fantasies become real.

Here's Marsha not long before

we took off for London,

Scotland, Switzerland and Paris.

Eight months pregnant

and she could still do a perfect

dive, and appall the other

folks around the poolside, who

weren't used to such an

unconventional woman.

People often thought I was the

wild one. I was the

comic book writer.

I wasn't even in Marsha's league.

Colin Campbell figured out a way they could afford to fly Marsha with me, and we flew to England with

Marsha seven to eight months pregnant. We had clearances from her doctor to take the plane. We made it

to Heathrow Airport without a problem. I will write another time about our experiences at the Con, and the

fans putting us up around England, and then up into Scotland.

The fans put Marsha and I through-out England when the 1978 London Comic Con was finished. I'll write about those kind folks, and how a jeep full of authoritative people zoomed up to our airplane on the runway and came to take us off, saying our baby would have to be born in England. True story. But another story. There's always another story. Here we are in Newcastle Fair Grounds, before all that tumultuous times, though.

The fans put Marsha and I through-out England when the 1978 London Comic Con was finished. I'll write about those kind folks, and how a jeep full of authoritative people zoomed up to our airplane on the runway and came to take us off, saying our baby would have to be born in England. True story. But another story. There's always another story. Here we are in Newcastle Fair Grounds, before all that tumultuous times, though. Still in Newcastle Fair Grounds. Laughing after a bleak time period, because this lovely lady is beside me.

Still in Newcastle Fair Grounds. Laughing after a bleak time period, because this lovely lady is beside me.In a Glasgow train station I saw one of the last comics I had written at Marvel, PALADIN, hanging up on wire strands the way I had first seen comics when I was a kid. It was a sobering thrill, exciting, and yet making me realize that indeed these stories reached places I never really realized they would, and that the investment of time and energy and emotional commitment were vindicated. It was also a book where at least a third of the beginning of the book had been re-written, although credited only to me, and that did represent my work, and that the untouched script survived only because the editorial wood-chucks ran out of time to change it.

I'm standing in a Glasgow train station where I am surprised to see a comic I'd written, drawn by Tom Sutton, hanging on the rack in Scotland. I haven't read this book in decades. I believe the first pages were rewritten, but the end pages are my finished copy. I loved seeing one of my comics in Scotland. It re-enforced, for me, the importance of comics, of how far we reached, and that standing firm on telling the stories, so that they were my stories, and not someone else's with my name on them, was a fight not without cost, but one I did not regret.

We reach so many people. It’s important to tell the stories the best you can, and leave it to others as to whether they love, like, don’t care, or hate them.

In years of writing comics, I have never had anyone come up to me and ask, “Why did the editor do this? Or the publisher? Or the artist?”

Here’s what they ask me: “Why did you do this, Don?”

You’re the story-teller. That’s your name and your life on that credit. You are going to be the one that has to live with what’s there.

I never made it to the Highlands of Scotland, but I still have a irrational belief that the Loch Ness Monster is there. I may be a mongrel, but you can’t have the last name McGregor and not feel that somewhere, deep in the blood, you are a Scot.

I know there were some folks at the London Comic Con who were appalled when they asked what Marsha

and I would name our baby when I told them “Rob Roy” if it was a boy. He’s Scotland’s Robin Hood.

After Scotland, we were bound for Switzerland, where my Grandfather Alfred Besson was born, and who

now stayed there during the summer. We would come back to England to depart back for the States, and

that became a traumatic time period where the unforeseen happened and we became held hostage. No,

really. American comic book writer and eight month pregnant wife forcibly trapped, without money, in

England!

But that’s another story.

There’s always another story.

Let me know if you want to read about it.

France has a reputation of diffidence to its tourist trade, if not even hostility. It’s paradoxical in nature given the Statue of Liberty and the liberation of Paris during the Second World War and the love for many American Pop Culture icons, befitting the nature of this piece about how I came to go from the ovations of an audience at the London Comic Convention after an hour-an-a-half stage show to meeting fans from different countries to Switzerland and then to Paris, while we had no idea how we were going to pay the rent when we got back to the States. It’s emotionally destabilizing.

Marsha and I took the boat from England to Calais after leaving Scotland.

Marsha looking radiant as she poses on the boat from Dover to Calais. She could turn the heads of men and women, wherever she went, even at eight months pregnant.

Standing at the railing on the boat from Dover to Calais, the wind whipping about me, the sun shining off the water, dressed in a red ruffled shirt, subtler than the ones I wore in my first visit to Greenwich Village where I knocked over one of the motorcycles of the Hell's Angels. That's another story. Proving, I guess, there is always another story.

Posted on the walls of the ship were notifications sternly warning about bringing animals onto France’s shores. We took photos on the trip from one country to the next, a short journey that we would soon discover landed us in a vastly different place.

When we stepped off the boat from England into the customs office in France, it was like entering a completely separate world. The barrier of a common language was immediately felt. There was no one we could ask where to go next or which car we needed to catch our train to Switzerland.

When a man (who looked like one of those burly, sullen dockside workers in B-movies like Charlie Chan or Mr. Moto, where the fog is impenetrable and the danger is always a heartbeat away) confronted us, and without a word grabbed our luggage and threw them onto a large hand truck, as if that was the way things were done, no questions asked. He hustled off. We didn’t know where he was going with it, or how far away the train was that we needed to take through France to get to Switzerland, I’m not even sure we were yet aware that some train cars disengaged at various stops. Getting on the train, but on the wrong car, could mean you would never reach your destination from here to there.

We entered a building and the large man didn’t. We had no idea where he or our luggage was headed. We stood in a line to have our passports stamped, and when we had passed through customs control, we saw our sullen man again, staring with dark, distant eyes, standing with our luggage on the large hand truck. The man nodded curtly, his eyes never changing expression, then spun on his heel and led us through a large doorway. Once through that entrance, we immediately saw the train platform, only five steps away on the French side of the boundary.

A long train was on the tracks, hissing, and looking like a dusty version of the Orient Express. I’ve always loved the sound of trains, it reminds me of playing around train tracks and high trestles over shallow rivers in Rhode Island, where I was forbidden to be as a kid, and was one of my favorite places to be. Under the trestle, the heavy train cars would fill the world with thunderous sound as they roared inches above my seven year old head. And as I grew older, it was the trains of movies and television that gave them a sense of intrigue: Hitchcock’s North By Northwest. Fleming’s From Russia, With Love. Bill Cosby and Robert Culp taking the “Night Train to Madrid” with Don Rickles on I Spy.

The man pushed our luggage up the platform for perhaps the length of three train cars and stopped.

This was it!

We had no way of knowing if this was the right car for our destination.

I asked the man with the sullen face, now indifferent eyes, “Are you sure this car goes all the way to Switzerland? See, “I tried to explain in damning-American, New England accented English, “we’re not stopping in Paris yet, and not all the cars go to Switzerland. Some of them disengage at Paris, and I want to make sure we have the right car.” I did a lot of talking with my hands. Some people have commented I couldn’t talk if I didn’t have hands.

The sullen man’s dark went impatient. He stabbed a finger at the car, dumped our luggage off the hand truck, and held out a hand for payment. The dark eyes now read clearly, “I dare you not to pay me!” He was sweating dirt. His blue shirt was mostly the color of grease. He barred the entranceway to the train.

We had some French currency, but we did not really understand the monetary exchange. I had no idea how much he thought was fair payment. I felt uncertain and helpless. Even talking with my hands wouldn’t help much. When you went to pay for something, you just had to hope in your head, “Please, don’t hurt me too much.”

Marsha gave him some money as I struggled to pick up the luggage. He looked at the money in his hands,

and straightened on the stairs to the train. He began to speak loudly, in French, shouting and pointing at

the money in his large palm. He shook his head violently. He would not let us pass.

Marsha asked, “What’s wrong?”

His voice became gruffer. He knew a little English. “Not enough!” his voice roared into the train-hissing air. “Not enough!” He followed that with another torrent of French, word I did not comprehend but the tone of threat and disgust clearly communicated.

The train whistled, talking of departure.

It was hot, and suddenly there was intense pressure about us. I knew of no law that said, even here, that you had to pay extortion to men picking up your luggage without your even having asked them to do so. I was also starting to get nervous since up and down the station people were struggling to haul their luggage onto the train. Steam billowed into the summer air.

I went to step past the man and his huge frame hustled in front of me, using his size as a blockade and threat. I wanted to tell him that I would have carried the goddamn luggage myself if I’d known it was only a building length away, and that this was a helluva greeting to his country.

He mouthed words in French, with an ugly twisting of lips. He knew the English words needed to get across what suited him. Marsha asked him how much more he wanted. Marsha would make a beautiful diplomat.

A loudspeaker spoke French words, probably announcing how imminent the train starting to move would be. I had a cramp in my right hand from the large suitcase handle digging into my palm, and an ache in my left armpit from the satchel slung snuggly under it.

Marsha held out money in her hand. With a snarl, an actual snarl (you don’t have to understand a language to recognize a snarl) he grabbed money out of her hand and stalked away, whipping up the hand cart onto his shoulder.

Well, hello, France.

The long train eventually made a stop in Paris.

Neither of us had eaten, and we learned we could buy some food while the train was in the station. I was reluctant to leave Marsha in the train compartment, but I knew we weren’t arriving in Switzerland until morning, so with trepidation I left her, stepped off the train into the immense station. The top of the building had high windows, shafts of light streaming down from them into the cavernous area filled with a maze of trains, the mingled roars engulfing the entire world.

I found a place to buy some sandwiches and what I thought were sodas. I asked for Ginger Ale, since I couldn’t find a Coke. The person selling the food and drinks had a look on his face, claiming he didn’t know what Ginger Ale was with a shaking of his head. The bottle was green. Time was running out. I handed out money with that “Don’t hurt me too much” look. I got a disdainful look back.

I hustled back out into the cacophony of numerous trains taking off, and idling. Now, I can get lost most anywhere. If I am at an intersection, and the choice is to turn left or right, and I have a 50% chance of getting it right, if there’s any betting on whether I choose the right direction, take the bet against me, because 90% of the time, I swear, I will be wrong.

I was a little concerned about finding my way back to our train in the labyrinthine platform, but I found it. Only to see the cars disengaging, and taking off in different directions!

Leaving without me!

Leaving with Marsha on the train!

My heart was pounding. I was running after the train with my hands full of sandwiches and bottled drinks, my shouts to stop lost in the thunderous train racket, metal wheels screeching off metal rails, steam hissing like serpent’s voices to the high ceilings.

I watched the train take off. I stood, breathing heavy, eyes wide, having no idea what to do. Someone who spoke English came up to me and saw the panic in my eyes and took mercy and told me not to worry, they were just attaching the different cars to different trains, and the one carrying Marsha would eventually come right back to the passenger car it had originally been attached to.

Train cars hitched to other train cars with shrill couplings. Some trains went backward to find their mates.

I stood and waited, clutching the bottles and sandwiches. Finally a train came backing up toward me,

clanked heavily into a waiting passenger car, metal gears locked, and Marsha was back!

When we were underway again, and rejoined, we sat in the train compartment with other people and started to eat our sandwiches. I thought I had put mustard on my sandwich, but it turned out to be some kind of horse radish concoction. It burned with the heart of dragon flame! My eyes went watering. I was gasping for air. The burn seared right into my lungs. I twisted open my Ginger Ale and swallowed deeply. Except it wasn’t Ginger Ale. It was some kind of Bitters for alcoholic drinks, and I choked on it, the fire not extinguished, my wet eyes wide, the bitter liquid spewing out of my lips, as in a great comedy take, my throat spasming, closing as if I’d drunk alum.

Everyone in the compartment thought this was pretty funny.

Laughter accompanied the acid burning my throat and insides, tears streaming down my cheeks, which was even funnier to some. Maybe Don Rickles was on board this train. Marsha thought it was laughing out loud funny, as well, until later in the night, when she could not get comfortable due to our son moving about under her rib-cage.

I found an empty car in First Class, and I took Marsha in there, and she was able to lay down, with her head in my lap until we made it to Switzerland.

I stroked her soft hair and she finally slept, and I sat gazing down at her, my fingers still softly moving down the doe-brown strands. Her face looked so calm and lovely in the moving lights and shadows. I sat that way until morning.

My grandfather, my Mom’s dad, Alfred Besson, came from Switzerland, and he was supposed to meet us at the train station. I can’t recall why, but he wasn’t there when we arrived, and I had to call my Aunt Louise, the woman who my Mom was named after, and try to find out where Grandpa was. She only spoke French. I only spoke English. My Grandfather could speak English, French, and German, and think in all of them, too, but no one apparently knew where he was. I had my name to give her, and the word for train station, and that was it. Eventually everyone managed to connect, although not until after I had bought what I thought were hot apple turnovers that turned out to be to be hot pork pies.

Leaping off rocks in a single bound in the Swiss Alps. I have no recollection of this. People have come up to me many times telling about me going over tables at comic conventions and come fighting out of elevators. I did so much of this kind of thing, had no inclination I was going to do it 10 seconds before I did, and forgot it 10 seconds after that I don't remember it. But in my head, I'm still that guy. But know I better not try it, because now, I'm going to get hurt, bad!

Here I am with my Grandfather, Alfred Besson, who took Marsha and I all over Switzerland before giving us enough money to spend a night in Paris. I don't know if this is before or after I jumped off the rocks.

My Grandfather took us into Apple, the town where he was born. He had been sent to the United States as a young man by his parents who wanted to get him away from an older woman. He ended up in Rhode Island, and when my Mom was 13 years old, my Grandmother had to drive him to the doctors. He was Hemorrhaging from throat Cancer. Blood gushed over the car. The doctor didn’t want to touch him. A police car had to take him to the city, Providence, blood awash on their leather seat, his body trembling.

From what my Mom was told, he had the first successful throat Tracheotomy in Rhode Island. What that means is, he was the first one who lived. Since they had little money, my grandparents paid the surgeon by baby-sitting his child while he went on a European vacation. Try pulling that off in this day and age.

When I knew him, my grandfather had a hole in his throat and always spoke in a whisper. He went from almost dying, losing his voice, but not giving up cigarettes, and took over a business which was going bankrupt. He travelled to New York, and in that hoarse whispered voice went to meetings to drum up a clientele. He had become successful, starting his own business, after Death had been close in the 1930s, and by the 1960s his company printed the patches the Astronauts wore to the Moon.

I don’t recall how often we went up to my grandparents place when I was about 6 or 7, but whenever I did

my first place to go was into one of the buildings on their property, behind the main house. He now had a

lot of land, a lengthy lawn with a goldfish pond surrounded by pine trees where goldfish were frozen in ice in

winter and stunningly started swimming when the ice thawed. My Grandmother had flowers

Growing up the driveway that circled about the house, and grew rhubarb on the other side driveway, a huge

“U”, but with so many buildings in the back you could only notice this from air. He tended bees and when I

was young and saw him in the white protective suits always thought of the Superman TV show, because it

looked like a radioactive protective suit. There were incubators for baby chicks off a tool room house. And

garages. And chicken coops over the back hillsides. There were a number of inter-connected low buildings

and garages, one with a large roosting room for more chickens and eggs. Beside that was a smaller room,

a storage place, one that drew me like a moth to flame, where, among other things, he stacked old

newspapers high.

My Grandfather used to get the Sunday News. This is during a time when my love for comics had already taken hold in my brain and heart. My first order of business when I got to my Grandparents was to go into that building, and search diligently through the heavy stacks of paper, looking for the Sunday comics, searching for the tell-tale color, admidst the smudgy gray daily Rhode Island newspapers, and trying to slide them free from the papers above, without ripping that treasure trove of text and illustrations, and hopefully not toppling the newspaper mountain down on my head.

In 1951, I spent many hours prying the colorful sections loose, and reading Chester Gould’s Dick Tracy as Bonnie Braids was abandoned by Crewy Lew for the wolves, and Dan Spiegle’s Hopalong Cassidy would topple with his horse, Topper, off a ripped apart bridge into the ravine below!

I would continuously wonder what happened in the Dailies. The curiousity of the story-teller already fierce in my psyche.

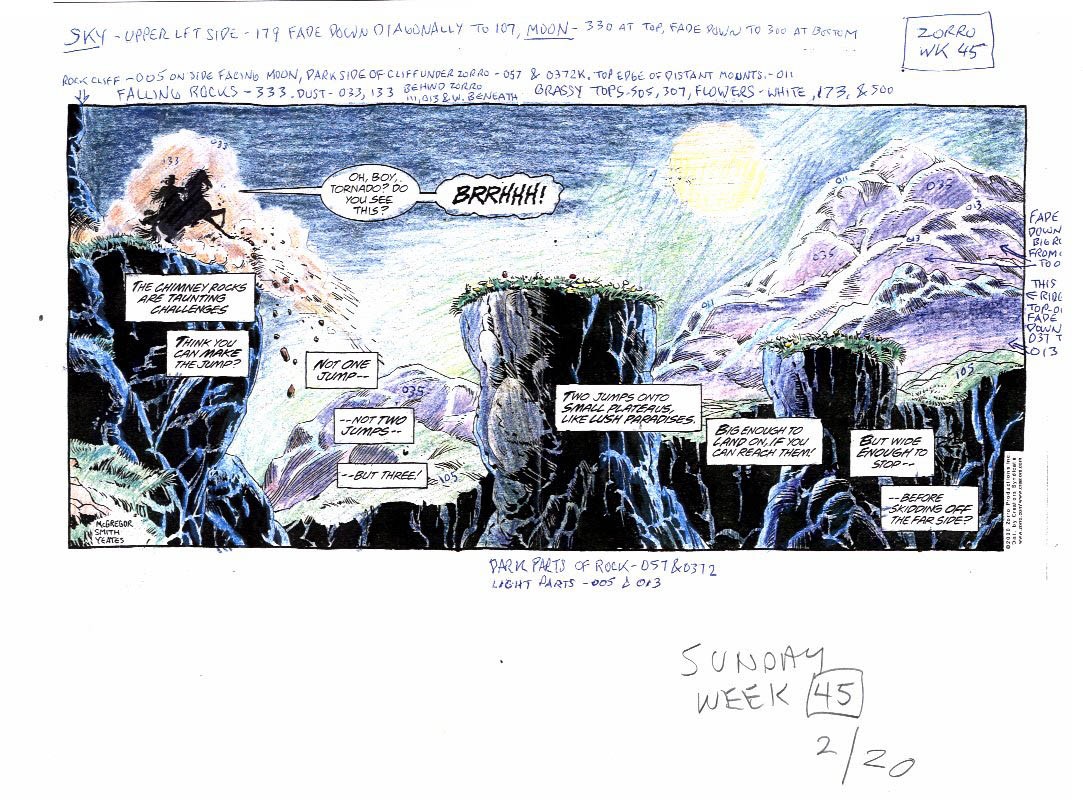

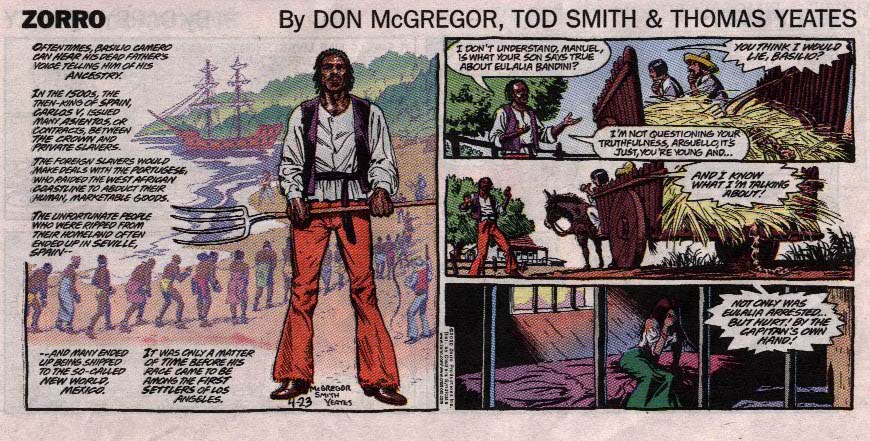

I still recall those Sunday News comics fondly. It was something special to me when my own comic strip, Zorro, with Tom Yeates saw print in that Sunday comics section decades later. The six or seven year old would never have believed such a thing possible if you’d told him he’d be a part of the Sunday News comics section one day.

Being in those New York comics had an absurd amount of emotional impact on me, and I treasure the chance to do those strips to this day. In the world of comic books, I might as well have died. Comic books and comic strips seldom meet, even if the News is brought into the Marvel and DC enclaves by many employees.

I have never understood the division between the two, the other scarcely recognizing the other.

In his home town, my Grandfather Besson took Marsha and I to the town church where they had excavated

a few years back to add a new attachment to the building. We went down into the musty cellar, and its dirt

walls, where human bodies had been un-earthed. There is something starkly mortal when you hold human

bones in your hands, knowing these once belonged to people who had lived, centuries before.

It was quiet in the tiny tomb speaking of life and death and time and history.

The bones did not testify to what these people thought or did when they were alive, but spoke loudly to the continuum of the human species, that they were, just as we are now.

The experience stayed with Marsha and I.

Marsha standing in the musty tomb where human remains were found. A linkage with the past with the future of life within her.

I had never met a woman like Marsha, who defied description. She left her home state without even a job to come to Manhattan. I didn't do it until I had a job at Marvel Comics offered to me, even if it was at the paltry sum of $125.00 a week. Try living on that in New York City, even in 1973, which is when I first left Rhode Island. Marsha is walking a Swiss Castle Gang Plank. Don't fall in the water, Hon. Even then we were told it was really polluted.

My Aunt Louise made us dinner, and it was interesting trying to explain to her what the Number 6 button I had on my shirt, given to me by members of The Prisoner TV series fans in England meant. My Grandfather translated my interpretations of Patrick McGoohan’s great, complex contemplation of existence and identity. I suspect for both of them it was mystifying in any language.

Here I am at a Swiss restaurant. My grandfather always ordered. Trust me. He almost always ordered these wonderful sausage dinners, a kind of sausage I've never had in the States. I said to him, "You aren't supposed to be eating these, are you, Gramps?" He said, in his gravelly whisper, "I like them." I got it.

A week later we had the opportunity to spend a day in Paris. We had arrived in Paris at nine in the morning after a long, uncomfortable night on the train from Lausanne. The budget guide tour book detailing hotel rates in Paris was out of date, but we found a place not far from the Jardin de Tuileries and the Louvre. The money situation was tight. As we studied the Mona Lisa, we both had bemused smiles. Here we were in Paris, lovers in the city of love. We had bemused smiles because we had come to Europe as the guests of the London Comic Convention and we had stayed in Switzerland through the courtesy of my Grandfather who had a chalet there, and we had a day and a night in Paris thanks to money he had given us. The bemused smile was that we could see the Mona Lisa, and the Arc de Triomphe and would soon visit the Eiffel Tower, and yet when we returned home we did not have the faintest idea of how we were going to pay the rent.

The paradoxical extremes of being a freelance comics writer in full effect.

We may have been paupers, but what a holiday!

We went into one of the tiny stores and bought sandwich meats and long loaves of bread, and we sat on the grass near the magnificent statues and had our lunch. You could dislocate your jaw trying to chomp into top and bottom of the bread.

Afternoon, when the sun is still out, and we have no idea what awaits us at midnight. Marsha chomps on a huge Dagwood Bumstead sandwich on French bread. Size doesn't matter to her. She is outside the Louvre, where she will try to teach me that there is more than just Pop Culture.

We walked through the Jardin de Tuileries. It was a bright August day, the flowers shouting in prescribed rows of brilliant color. People sailed boats in the small fountains, and it reminded me of the old Avengers television series for some odd reason.

Marsha naps in the Jardin de Tuileries, looking lovely. In those days, Marsha could put her head on her hands and immediately go to sleep. If I put my head on my hands only my hands would go to sleep.

We reached the Champs Elysses. The Times Square of Paris. The sidewalks were crowded with tables and chairs outside the cafes. It was cleaner than Broadway, but the place had the same tumultuous air of immediacy.

Paris is definitely a city, the way Manhattan is a city. You don’t have to see all of it to recognize that fact. It is not crowded buildings, or skyscrapers, or cement that make a city, it has something to do with its pulse, something to do with what you sense in the air. It is exhiliarating, demeaning, joyous, harsh, a kaleidoscope of sights, sounds, emotions. It is the best and the worst, from one block to the next, sometimes right beside each other. Paris had it, plus a sense of tradition that Manhattan cannot maintain. Manhattan is an island, and it is a city of change, and if you have no room to expand then that change continually has to take place within the confines, and much of what was there vanishes.

I have seen an entire block between 42nd and 43rd St off Time Square disappear. All the skyscrapers, gone. When they do it, in this city that never sleeps, and the place where it does not sleep the most is in the heart of Times Square, is beyond me. Yet, it happens, hardly anyone notices, and it doesn’t even make the 11 o’clock news.

Paris has a feel of history and endurance. A city of splendor and squalor.

We were saving our money for a night-time sidewalk dinner, so I went into the familiar McDonalds on the Champs Elysses, trying not to think of the multi-million dollar ad campaigns at home that implied that Big Macs were what made America great.

There was a television set hitched up above us, and at first I thought it was a monitor to make sure no one was smuggling away any precious McMuffins. It wasn’t. The screen was showing previews for some movie. And there were men and women up there on that public viewing screen, in the nude, fondling each other, while a voiceover in French breathed, tense with eroticism.

Sex in McDonalds!

You’d never see that in the States.

We travelled the Seine at sunset on a boat that I thought served dinner. This turned out to be a false

impression. We stepped onto a glamorous boat, replete with strings of lights and darkened bar area,

bought our tickets and ended up escorted onto a tour boat with rows of bus seats. The sun went down with

golds and reds and a flair for romance, though the seats made it difficult to pursue the idea.

We rode the elevators up the skeletal metal frame of the Eiffel Tower at last light. The wind reverberated

off the thrusting phallic structure. The man who envisioned this must have been denied an erector set when

he was a child and had a complex about it for the rest of his life. He compensated for it in a big way.

It was eleven o’clock before we descended from the lights of Paris, seen from high above, and walked over

the bridge and made our way along the quiet, nearly deserted quays. I was looking for a dinner boat,

remembering Modesty Blaise dining elegantly with Sir Gerald Tarrant on such a floating restaurant, and

other memories of Cary Grant cruising the dark waters in lighted festivities with Audrey Hepburn in Charade.

The boats were all dark, empty. The water chatted against the wood pilings.

It was going toward midnight, and we were both tired and hungry. Marsha was huge the way eight month

pregnant women can be, but she did not complain. She had enough enthusiasm for her, Rob Roy and me.

We found a sidewalk café that had a waiter who spoke English. He was excited when he learned we were

from New York. He wanted to know about Greenwich Village. His eyes were excited as he spoke its name.

It was a name that conjured fantasies for him, the way Paris conjured fantasies for some folks stateside.

We left the restaurant around one a.m. We had an idea of the general direction for the Champs Elysses,

and we set off in search of it. The streets here resembled the streets of Greenwich Village, twisting like cow-

paths, doubling around, lapsing into dark stretches, bursting into a series of nightclubs with music drifting

out of gay interiors.

Eventually we staggered onto the Champs Elysses. Marsha suggested we take the Metro, Paris’s subway system. I was not crazy about the idea. My first impression of Paris was that it could be an unpredictable as Manhattan. I might ride the trains at 3 in the morning (and often did) in Manhattan, or even strap on six- guns and play cowboys in Central Park (which I did during my initial forays into New York City, when I stayed with Alex Simmons or Billy Graham) but I did not do any of those things until I knew the terrain, or was with people who were hip to that environment. But I had to agree with Marsha. The money had gone quickly in Paris, strange coins and bills of peacock colors disappearing from my wallet. We had only a little over a hundred dollars to last us until we got back to the States. Taking a cab would be an extravagance we would have to forego.

We walked down the steps into the tunnels. There were several folks ahead of us. The tunnel curved into the unknown. At points the tunnel split in a “v”, at others, side tunnels went their own merry way, all lit fluorescently, the lights reflecting harshly off the marble walls.

A trio of drunks moved into position behind us. They laughed the kind of laughter that goes along with pulling the wings off butterflies. Their shouts echoed off the ceilings, rang ahead of us. We couldn’t understand a word of it.

When you are in a strange environment, one where you do not understand a word, except for “Oui,” and that only because it is the title of a magazine, when it is also after one in the morning and your only company is a trio of drunks shouting and whooping, when you are not sure which tunnel to take or which train to catch, it does a great deal to bring out your natural reserve of paranoia. Animals have this, also, but it then called self-preservation.

“I’m not crazy about this whole thing,” I said to Marsha as we reached the platform that should take us back to the Jardin des Tuileries.

“Don’t worry,” Marsha answered. “The train’ll come in a couple of minutes and we’ll be right back to our hotel.”

A train did come, on the opposite side of the tracks. A few people gathered on the platform across the expanse climbed aboard, the doors closed, and then the other side of the tunnel was empty, as quiet as a morgue at midnight.

A woman’s voice came over a loud-speaker, sounding metallic, like a phone company female computer. The words were in French, but they had been reduced to the impersonal precise quality of a feminine robot. The flat sounds echoed in the empty tunnels.

“Probably an advertisement,” I told Marsha.

She did not look convinced.

“Maybe she’s telling us when the next train is coming in,” I added, hopefully, looking up the platform.

It was then that I realized we were the only people on the platform except for two men standing way in the

distance. That was curious, I thought. Isn’t anyone else taking the train?

They pointed at us. One of the men laughed. The other shook his head. He gestured toward us again.

I looked at Marsha. She was sitting on the bench, her eyes tired. She wore a blue maternity dress with

white frills. I realized that my hands were clenched into fists at my side. I tried not to look at the two men. I

imagined they were talking about us. “Now that truly is enough of that, “I scolded myself. “That truly is

paranoia.” They were probably pointing at something past us. Out of the corner of my eye I saw the two

men dart quickly into a tunnel near them.

And then we were alone.

Even the metallic voice was gone.

The tunnels stretched; a silent tomb.

Come on train! I shouted the words in my head.

“Now what were those two guys up to?” asked the paranoid gremlin in my head, birthed by too many One-

Eyed Jacks seen in the comics world. “And where did they go all of a sudden?” Hmmm….

The silence seemed more ominous. Could silence become louder with the passage of time?

No one else walked onto the platform.

Finally I said, “Hon, I don’t think a train’s coming.”

“Oh, you’re thinking that too, huh?” Marsha said, calmly.

“Well, it’s been awhile.”

“Let’s see if we can find one of those booths and ask someone,” Marsha suggested.

I just wanted to move out. I didn’t like standing still in the empty tunnels in the early morning hours. Something honed from my recent years of wandering through Hell’s Kitchen and Harlem and Times Square in the early morning hours, when the predator’s come awake and are on the prowl.

We retraced our steps. I wasn’t about to go down the same tunnel as those two guys who’d been pointing at us had gone. We walked through the white glare, our foot-beats echoing faintly.

The lights killed all the shadows.

There was a dead, solitary sensation in the air. We reached the entrance, and in the pitiless lights, bouncing heartlessly off the white, sterile walls, all free from graffiti, we saw bars!

Metal prison cell shafts stretched from ceiling to floor!

WE WERE LOCKED IN!

I did not lose my world-famous cool, though it nearly suffered a heat stroke.

“This,” I said, trying not to let my voice quaver, “is probably not a main entrance. Probably what we have

to do is find a main entrance, don’t you think, Hon?” I suspect there was some pleading in my voice.

“I think maybe the woman who came over the loudspeaker was not doing an advertisement,” Marsha

answered, as we trudged back up the brilliantly lit tunnel, devoid of shadows.

Fear trudged with us, not just faint tendrils of suspicion, but one of Poe’s living entombment.

“What you’re saying,” I did not want to speak the unspeakable thought, but compulsion had its way, “is

that…”

We came to the main entrance. The token booths were empty. The cement floors looked reasonably clean. That was good. We might have to sleep on them.

We walked to the wide stone stairs leading to freedom.

Barred!

“I think…maybe…you’re right.” I was afraid I sounded a little like Don Adams in Get Smart.

I grabbed the bars, wondering if I looked like Jimmy Cagney in all those 1940s Noir Crime films. I was tempted to shout, “Top of the world, Ma!” but since we were imprisoned in subterranean labyrinths I rejected the impulse. Besides, the Don Adams comparison seemed more apt.

I stared upward, willing my corporeal being through the metal shafts. Maybe a Killraven inspired notion. Nothing happened. Damned comic books!

I continued to look up the wide stone steps, now denied us, and at the sidewalk level something moved. What was it?

Legs!

Legs?

Well, if there are legs then there must be people up there! Now I could make out something more, the faint light of a newsstand at the top of the steps.

“We’re saved!” I yelled.

Marsha and I began to shout. “HELLLP”

In my head I added “SOS” and “May-day!” Anything that would bring the crowds storming down. Surely someone would say, “Don’t worry now, folks, we’ll have you out in a jiffy!”

First one head poked down, then disappeared. It reappeared, joined by a second head. Legs began to descend down the stairs, four, ten, sixteen. The figures walked up to the bars, looking at us on the other side, this crazy American with the peach colored ruffled shirt, and the woman who was obviously as pregnant as one could get without delivering.

“We’re locked in!” I said desperately. “We can’t get out!”

“Help us,” Marsha urged.

They did not understand a word, not even “Help!” Or maybe some of them did. They were young men, and some started to grin as the realized what the hell was going on, and some started to laugh. A gang of young males, now many with indolent sneers that transcends cultures and looks mockingly out over the world. It is a look without compassion, one of disdain. One of the guys said something in French that had the word “Americans” in it.

The young man turned to us, his face with a hard smile, as he jerked a finger across his throat as if slicing it, and then he pointed at us and hard laughter followed the hard smile. The others joined in, the gang mentality on full exhibition.

“But don’t you see,” Marsha pleaded, “we’re stuck here. Can’t you get someone to help?”

The mood was turning ugly. They jeered and shook on the bars, and they reached through the bars,

trying to grab Marsha, like Zombies in George Romero’s Night Of The Living Dead. I pulled Marsha away

from the bars, suddenly glad the barrier was there. This was not going to be the way to be rescued.

We backed away away from the gate as the group howled insults we did not know by word, but could feel

by tone.

We walked out of their sight over to the empty toll booth and sat down, backs to the wall. The laughter faded. The gang was getting bored. Time to saunter up the steps and continue their shambling through the dark, trying to find something else that could hold their boredom at bay.

“Look,” I said, calmer now than I had been when we first learned that we were locked in, “there are lots of off-shoots that lead to other platforms. You stay here, and I’ll run down them all. One of the token booths must be open.”

I took off down the nearest tunnel, listening to my running footfalls sound ahead of me, on top of me. I explored each branch, each locked stairwell. I thought of the two guys who had been gesturing toward us, and all those dark, menacing entertainment suspense stories chased after me, the innocent couple unable to escape the half-crazed, insatiable, unbelievably ugly rapists and goon member squads.

Another old favorite scenario reared its head, another Pop Culture refrain. The husband and wife become trapped in some grim situation, and the woman is imminently due to give birth, and wouldn’t you know, as soon as they are stuck in the middle of nowhere, when things couldn’t get worse but then do and there isn’t a pediatrician or obstetrician in sight, she has her first labor pains. Oh! Oh! The scenarios ran through my head as I ran from tunnel to tunnel, found exit and exit, all barred.

I trudged back in defeat. I walked for what seemed a long time in that pitiless light. I stopped, stricken. I was lost! I was what? Lost! Lost, you idiot! Lost from running down all these tunnels that look alike, thinking all those dumb thoughts while hustling, that kind of lost!

Oh fuck!

In panic I began running again, now with real desperation. Something was inset into the wall up ahead,

something metal and red. I stopped by it. An alarm! Hot damn! All I have to do is pull it and the Calvary

comes rushing to the rescue. Great!

I yanked, hard!

BA-WHAMP! BA-WHAMP! BA-WHAMP!

The siren ripped the silence, filled every tunnel, tore into my ears. I grinned. All right, Calvary, do your stuff!

I took off down the corridors again, turned right, left, and right again.

BA-WHAMP! BA-WHAMP!

I ran out onto a train platform and saw the token booths. Marsha was standing near them, looking confused. She saw me and the anxiety left her face. I ran to her.

“That noise…I didn’t know what had happened to you,” she said.

We held each other very tight. Her stomach seemed to pulse.

“I pulled the alarm. It’s going to bring the Calvary,” I told her, smiling idiotically, and then felt her stomach with the palms of my hands. My smile strained. “Not having any contractions, I hope.”

Marsha laughed, released from her lonely vigil at the token booth.

“What makes you ask that?” She had to shout the question to heard over the B A-WHAMP! BA-WHAMP!

“Oh, nothing,” I replied. If I told her all the crazy thoughts going through my head, I figured she have

patted me thinking Don reads too many comic books and watches too many movies and TV shows.

Marsha had a thought. I don’t know how anyone could think of anything with that infernal BA-WHAMP bouncing off every wall, continuously. The only thought I had was the faint suspicion that the Calvary was not going to charge up the subway tunnels, that there was no one else in this vast labyrinth of bright sterile walls, no sanitary men sweeping the cement, no maintenance folk prowling about the trestles, the way you often saw in the early morn hours in Manhattan, no one but the two of us in the whole intricate maze of the subway system of Paris.

And now we would have to listen to BA-WHAMP! BA-WHAMP! all night long, ripping into our ears and jangling our brains, and that by morning we would be reduced to gibbering numskulls. Okay, Marsha’s smarter than me, she has the degrees to prove it, maybe not her.

Marsha dug through her purse and came out with our tour book. She said there might be some kind of emergency number in the book that we could dial and get help. And sure enough, there was! We searched and found some pay phones on the walls reflecting all the light.

Now, if only we could find the correct French change to use the damned thing! Nothing is simple when you are a stranger in a strange land.

I pulled a handful of change out of my pocket. The coins were all different sizes, different shapes. Was a French phone-call about the same cost as one in the States? Did the smaller coins denote lesser value? We tried the coins. Eureka! One of them worked, but it was the only coin we had of that size. If we became disconnected during the call, that was it. We were trapped! We were screwed for the night!

On the other end, the phone rang. Once.

BA-WHAMP! BA-WHAMP!

Twice.

BA-WHAMP!

Someone picked up the phone on the other end. I signaled Marsha with a thumbs up sign. She flashed me an OK sign back.

The man must have said something like, “Hello,” but you could have fooled me. I knew how to say “Bon jour,” but that did not seem appropriate. My euphoria left, like a rat deserting a ship. The man on the other end of the emergency phone only spoke French. I only spoke English. Oh, oh.

I heard that old line, “What we have here is a failure to communicate” above the BA-WHAMP!

“We’re in trouble!” I yelled into the phone. He may not have understood the words, but the sound of panic is universal, it does not need words, only the specific crisis needs words and interpretation. I explained our situation. I could tell he didn’t know what the hell I was talking about!

He asked questions. I knew they were questions, I just didn’t know what it was he wanted to know.

Marsha pointed to the wall beyond the bars. The name of the station was there. Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Above it was the word “sortie.” Exit! It must mean exit.

“We…are…stuck…in the…Metro…MET…ROW…Stuck, with wife…wife have baby…BAY…BEE…stuck…no sortie,” I thought that was a good touch, throw a bit of French in there. “No sortie Frankling Delano Roosevelt Metro.”

I wondered what it was he thought I’d said. And why is it when the chips are down, and we can’t find a common link of language, whether it is with another culture or with children, adults revert to baby talk, as if somehow that will make everything clear.

We said the same things, a dozen times or more. What else was there to say? The man had remarkable patience. He did not hang up and write off this unwanted intrusion. I was afraid that a French operator would come on and say with schooled, implacable diplomacy, “I’m sorry but your three minutes are up!” I wouldn’t understand a word until the dead phone line reached my ear and left Marsha and I with the BA- WHAMP! BA-WHAMP! which still gave no indication of losing its enthusiasm for breaking down the tunnels about our heads.

The man left the phone. I did not know why. I looked at Marsha, trying to appear hopeful. She held my hand. There was the sound of a typewriter on the other end, in the world beyond the bars. The receiver over there banged once, and then a new voice came on, one that could speak English!

BA-WHAMP! BA-WHAMP!

Not ten minutes after I had explained our plight again, a group of men, dressed in work uniforms appeared while the alarm kept score. The leader spoke in French and was obviously wondering how in the hell we managed to get ourselves locked up in the Metro. He sent one of the men away, I didn’t need to be a translator to get the idea. “Get over there and shut that Godawful racket off!” or some variation of such. They did not have the keys to let us out, but within minutes some policemen came down the steps where the punks had been an hour earlier. One had some keys. Keys! Keys that he put into the lock, twisted, and the stairs beckoned us out to the night skies of Paris. The one policeman who could speak English asked us how we had managed such a trick as to get locked up. We shrugged. They all shook their heads. With those Americans, you never know, their eyes seemed to say.

These days, it would not surprise me if they would have thought we were terrorists.

We didn’t learn until we were back in England that New York City has the only subway system in the world that never closes, that is open 24/7, and for one fare, you can ride forever, as long as you don’t exit the turnstyles.

The English speaking policeman told us to stand in the middle of the street and a taxi would stop for us. Looking bedraggled, we crossed the lanes, and our rescuers walked away, chuckling. Tell the wife about this one.

A taxi came. I went to open the door for Marsha, tired, weary. Across the street some bon vivants, ending a night of frivolity, raced to the opposite side, flung open the back door and four of them jumped gaily inside, squealing and laughing. The taxi left us standing on the meridian. I looked at Marsha. I shed my civilized behavior, like a rattler leaving behind dead skin.

A second taxi pulled up to the island. Across the street, two men and a woman rushed for the opposite side. I stepped out into the street. My hands were clenched into fists. Something in my eyes made them stop. They recognized that look, it transcended language.

“Don’t even think about it,” I said, quietly.

The man’s hand released the door handle. They backed away from the loco American, knowing there would be a lot less grief for all concerned.

Marsha and I took our seats in the taxi, gave the driver our hotel address. The capper was about to happen, in the best Buster Keaton/Harold Lloyd tradition.

When we reached the hotel, we trundled out. The taxi pulled away. I went to the hotel entrance. I grabbed the doorknob. I turned it.

And stopped.

I couldn’t believe it!

They had locked the hotel up for the night!

The both of us couldn’t help but laugh.

-FIN-

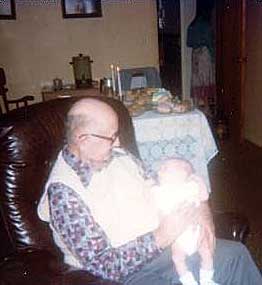

My grandfather Alfred Besson and my Mom and Dad's house in Rhode Island with his baby Grandson, Rob Roy McGregor.

Mike Rockwitz writes:

I just read this Don-it moved me. Hard to describe how - but it did - in a great way.

Such a great husband and father, and an amazing writer too. What a creative spirit - the energy I felt from you courses through your words. Amazing.

Happy Holidays to you and the family

Mike R

Don's reply:

Thanks so much, Mike. Marsha says you should come back over and we should have another all night

coloring session the way we did when we worked on a chapter of PANTHER'S QUEST.

Would it be okay to print your letter on the Metro piece, Mike? I can't put it up there, but I'm sure Malcolm, who puts these things together can, and hopefully folks will realize they can have permanent comments as opposed to here and gone comments on Facebook.

Happy Holidays, Mike! Working with you and Terry on the Panther comics was the best working time I ever had at Marvel. Well, okay, with Archie on the graphic novel, as well.

Don

Tony Isabella writes:

I read of your adventures in Paris and the image that came to mind was that you're Harvey Pekar if Pekar had been more adventurous and less fearful of life. Comics versions of these tales could be American Splendor ala McGregor. They are funny and warm and tinged with such enough scariness to relate to the nasty chaos of modern life. With Harvey's passing, too young for a guy who was still knocking them out of the park, there will probably be a dozen guys pitching their versions of Pekar to the book publishers. And none will exhibit anything close to the genius that was Pekar.Your tales could be in that arena without just imitating Pekar.

I wish I could cast the movie. But who could play the young Don McGregor as well as you did?

Bruce Canwell writes:

Hi, Don—

Thanks much for sending me your "Paris Metro" essay — I've yet to visit Paris (someday, someday), but I've been to Scotland a few times, and Glasgow is one of my favorite cities. Not as pretty, but also not as pretentious as Edinburgh; more welcoming than Aberdeen, with its cold, granite, Gothic facades. Glasgow struck me as having a great and eclectic arts presence amidst its working-class exterior; a real city with soul.

During my inaugural visit, I saw Fellini's AND THE SHIP SAILED ON at the Glasgow Film Theatre on Rose Street (and had a Scotch in the little café/bar affixed to the theatre before the film); saw SUNSET BOULEVARD at the same theatre the last time I was in town. Once spotted "Don’t Yield — Back S.H.I.E.L. D." chalked onto one of the exterior stones of a building on West George Street. Was in town during Bank Holiday and a long parade threaded the main streets, with various clubs' bands and pipers part of the procession — I laughed a lot when a particular brass band passed me by and one of the trumpet players abruptly broke ranks, ran from his fellows, and ducked into the pub on the corner for a short glass of fortification! Great memories that make me wish I could be on a plane bound westward right now…

Aside from stirring up my nostalgic leanings, I nodded at your lines, "We reach so many people. It’s important to tell the stories the best you can, and leave it to others as to whether they love, like, don’t care, or hate them … You’re the story-teller. That’s your name and your life on that credit. You are going to be the one that has to live with what’s there." Ain't it the truth! Dean and I have been sweating bullets driving our big Alex Toth biography book to completion; I was on the phone with the younger of Toth's two sons and he remarked on all the care and attention that goes into these final stages. "Once it goes to the printer, that's how it looks forever," I said to him, "and the goal is to make it look perfect." You were teaching me lessons like that all the way back in the pages of PANTHER and KILLRAVEN, then in SABRE and DETECTIVES INC., and in a whole lot of other stories besides, and I appreciate reading the reminders these days more than ever.

Speaking of the Toth book, we gotta make sure you get a copy — a McGregor pull-quote would look great on the back cover of our sequel volume!

Meanwhile, here's hoping you and yours enjoy a warmer and less inclement February than we've had so far in 2011. January has been like living in the middle of a snow globe!

Best wishes, as always—

-- Bruce Canwell

Associate Editor

5 Danforth Road, # 6

Nashua, NH 03060

I have often found that life as a Freelance Writer was filled with paradoxical extremes.

You could be exalted by finding a copy of one of your comics in a Glasgow, Scotland train station and realize how far the stories reached while wondering how you could retain your individual voice as a story- teller.

You could be at a Comic Convention and having people tell you with heart-felt, heart-TORN sincerity, what your stories mean to them, tears in their eyes bringing tears to your own eyes and yet not know where or when you will get to tell the next story.

Strangers will know you and care for you passionately, and you have never seen them before.

In 1978, I was invited to be the Guest of Honor at the London Comicon.