The Official Website of Don McGregor

The Official Website of Don McGregor(A brief excerpt from The Variable Syndrome ©1980, 1999 Don McGregor)

I remember a Christmas season right after the time period I'd written the Black Panther for Jungle Action and Killraven at Marvel Comics. I was in the process of creating Sabre and hoping Dean Mullaney, the publisher of Eclipse Comics, and I were right, that there was a sufficient market place to sell comics outside of the traditional establishments. But Sabre was two years in the making, and it was only one book where the other series had built on over two years worth of stories. It was the middle 1970s.

The money situation during that time period was desperate, to put it mildly. I was with my daughter Lauren on one of our court-appointed weekends, and we walked past holiday hawkers who stood on the Greenwich Village street corners shouting their wares: Christmas trees imported from upstate New York.

"Getcha self ya own Christmas tree, right here! We got the best Christmas trees there is!" shouted a man with three days dark beard and raggedy blue sweater drooping over his apparently marsupial stomach.

Lauren was six years old, alive with Christmas.

I stopped walking, feeling Lauren's hand in mine, remembering a jumble of my own childhood Christmases. There were broken pine branches scattered over the broken, grey slabs of sidewalk.

I had twenty dollars to my name, twenty dollars that had to last through the week, or maybe more; but Lauren was only six once, and very fiercely I wanted her to have a Christmas tree at her dad's house. Intermingled in those emotions was a sense of failure. I had the impulse to run to the comic book offices and tell them I would write anything they wanted me to write so that I could easily afford a Christmas tree for this six year old girl who held my hand and heart, and also so that I would not have to face such guilt and failure.

The man in the raggedy sweater looked at me through the dim light.

"Ya want one?" he asked, shaking one of the trees, a puny thing with scrawny branches.

More branches dropped and collected on the cement.

Lauren stooped and picked up a couple of greens, fingering the pine needles, her dark, wondrous eyes seeing shapes and visions I could not see.

She did not know her father felt like a loser on this cold night.

Twenty dollars in my pocket, I thought. But what the hell, I can survive on ten dollars for the week, maybe even five if I have to pay fifteen bucks for the tree. It'll be a tight week, eating Campbell's soup every day, but I can hack that.

"You want to get a tree, Harry?" I called Lauren "Harry" for Harry Houdini. I also called her "Cutie-kins," which I think she still likes to this day, and "Hon," and sometimes, "Wolfgang," long before she became a fan of Mozart.

"Can we?" she asked.

"Well, sure, but we have to pick it out, you know? We'll have to look them over." I answered, as the hawker scowled at me in the dark and shouted to other passersby to stop and look the trees over. I wondered if he also sensed that I was a loser.

Holding onto her branches, close to her chest, Lauren examined the trees leaning against the battered station wagon that seemed to match the raggedy sweater and the three days growth of beard of its owner.

"How much are your cheapest trees?" I asked, trying to sound casual.

"Twenny bucks!"

"Excuse me?"

"Twenny bucks!" He returned, louder, his eyes already dismissing me.

I felt as if I'd been shot. I knew I was taking this too hard, making too big a deal of it, yet depression hooked claws into my mind and unlocked vast stores of self- pity.

I walked over to Lauren who was judging those Christmas trees with dark eyes. I knelt before her, feeling very sad, as if not only her dreams but my own were endangered.

"Honey," I said, finding it hard to talk.

"Yes, dad?" she asked, turning to me.

I looked into those deep, dark brown eyes of six years, and I said, quietly. "Honey, daddy doesn't have enough money to get a Christmas tree. See, they're a lot of money, they're more than I thought, and well, dad just doesn't have enough…"

She smiled at me as if I was being much too silly. "That's okay, dad," she said, buoyantly. "Not to worry," and then she held out the two branches she had clutched to her chest. "See, I've still got my branches, and that'll be enough."

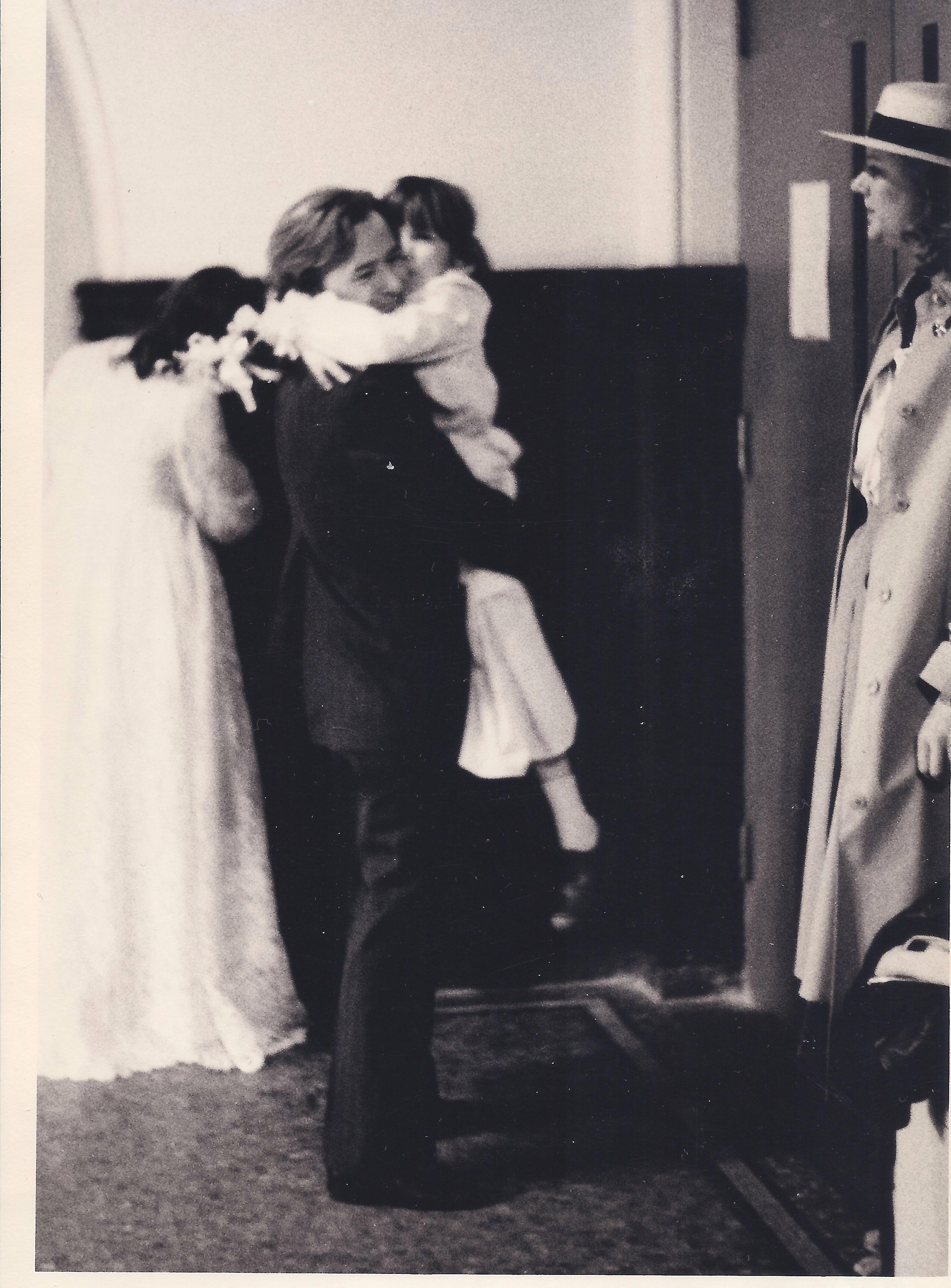

It was a Christmas story in some children's book, about the meaning of Christmas, with cute illustrations, except that it wasn't, it was Greenwich Village with shouts and curses and car horns  and grocery stores gone dark for the night, and there were no illustrations, there was only this dear daughter of mine whose words brought tears to my eyes I could not explain, tears that were a mixture of love and hurt and hope. I could not hold her close enough. She was six years old, she could not understand her father's tears, I'm sure, but she held me also, tiny arms stretched up round my neck, not precociously but innocently, with a love I felt I did not deserve and did not want to lose, ever!

and grocery stores gone dark for the night, and there were no illustrations, there was only this dear daughter of mine whose words brought tears to my eyes I could not explain, tears that were a mixture of love and hurt and hope. I could not hold her close enough. She was six years old, she could not understand her father's tears, I'm sure, but she held me also, tiny arms stretched up round my neck, not precociously but innocently, with a love I felt I did not deserve and did not want to lose, ever!

I write about it now so that I won't forget that time, and that some day she might read about it. I wonder how she will remember that night, if she will recall anything of it at all.

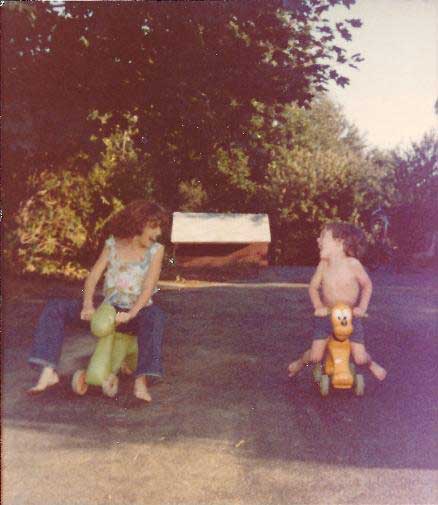

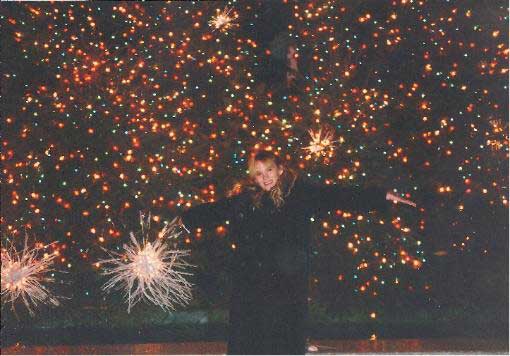

Here's Lauren and I today, with a photo taken by Carl Booth. She still remembers the Christmas tree night and recently told me what happened after the point this story ends. All of us here, Lauren, my son Rob, my wife Marsha and I, wish you all the best of holidays, whatever your holidays are, and however you celebrate them.

Comments

Joe Ackerman writes:

Aw, jeez! now you got me all welling up!

man, kids'll do that to ya.

You have a terrific Christmas, Don!

Don's reply:

Joe,

I'm writing this in the New Year, 2011. Sorry it took so long to get your letter up here. It's snowing outside right now. There are still blocks of soot-blackened snow the size of icebergs on sidewalks and street curbs and lanes. If you were to hit them with your car you'd feel like you crashed into a solid iceberg.

Lauren has just made a big move, from the East Coast to the West Coast, and as I write this, it is her first day back there. We talked for a long while yesterday, and I kind of wish I'd been able to get to her, to be with her for such a long week and such a vast change in her life.

And one of these days, when I'm with her, I'll have her talk about her memories after those dark moments in Greenwich Village. Someone once said to me they hoped they would have a time like that with their daughters. And I told them, You really don't, because if you don't have to, you don't want to have to live through all of that.

Don

Davide Cuccia writes:

That's beautiful! And it captures the essence of Christmas, the feelings of a child for the excitement, the smells, the wonderment of the season... without the commercial degradation of adulthood to tear away the dream. Lauren's empathy to just BE with her father, no matter how much money he did or didn't have to spend, touches on the simplest of emotions that, if we're lucky, always permeates the heart and makes the season special again, even for the cynics...LOVE.

For a special little girl and a special father who have a wonderful memory that's always theirs alone...a tip of my fedora!

My mother and I always shared the same empathy you invoked in your writing and remembrance, Don...and I find over the years no matter how many years pass since her passing, those dreams, those special memories of just being together, no matter how rich or poor, are the strongest, most pungent and enticing memories...they put me back in the spirit of the season, even during those years I don't particularly feel like it! Thank you my friend! Thank you!

Don's reply:

David,

Thanks for taking the time to write. I just spent Lauren's last Christmas in the East. She had more than one Christmas tree in the house. She and her Mom had baked I guess about a dozen different types of cookies over the past two months. Her brother, James, had made hot wine-apple drinks. And she and James told me why they hadn't seen the Paris Metro pieces, because both use Blackberries, and the screens are so small they really can't see the type on the Riding Shotgun sections.

James told me some sites are now making it so you can push a button to see it on an phone or IPad, or whatever the hell device one is using. But both made me realize that a lot of folks now aren't going up on their computers, they are doing it all over their mobile devices.

I've talked with Malcolm about this, and when he has time, we'll see what we can do about this, and also about getting replies up on donmcgregor.com a little faster.

Thanks, my friend.

Don

William McMahon writes:

As it seems in life we are Nautilidae; the small creature that spends its life secreting calcium to make a home. To the cephalopod, all it has is the humdrum existence. When we see the result, it's perfect shell; the Nautilus confounds any explanation. How can a Father be so blessed as to have the loving eyes that a daughter gives...

Thanks Don.

Don's reply:

And thanks to you, William. There are upsides and downsides to everything.

Costs we see, costs we don't see coming, and costs that are sometimes

more than we believe we can survive. The upside cost is having a son and daughter who still like to be with their dad, and still believe in me, even when there are times that belief could be shaken. And for readers who had taken the books to heart and followed them for so long, and let me know they despite the costs, they still had meaning.

Don

I remember a Christmas season right after the time period I'd written the Black Panther for Jungle Action and Killraven at Marvel Comics. I was in the process of creating Sabre and hoping Dean Mullaney, the publisher of Eclipse Comics, and I were right, that there was a sufficient market place to sell comics outside of the traditional establishments. But Sabre was two years in the making, and it was only one book where the other series had built on over two years worth of stories. It was the middle 1970s.