Will Eisner: the Artist Who Influenced You When You Didn't Know It

Will Eisner influenced me when I wasn’t even aware of it.

The reason this can be a truth is because Will influenced so many creative people in comics. So even if you hadn’t had a lot of exposure to Will’s work, the chances are you were affected by it, in some form, through another artist who had been influenced with Will’s work.

The first time I’d ever read The Spirit was in the Harvey comics reprints in the 1960s. I don’t know who chose the particular Spirit stories for those books, but they chose many of the most compelling and dramatically effect.

I suspect, at the time, I wasn’t aware that these stories were reprints of a weekly Sunday comic strip, although I might have been. Somewhere along the way, maybe after, maybe before, I had experienced a little of the Spirit and Will Eisner through Jules Feiffer’s The Great Comic Book Heroes.

I loved the stories in the Harvey Spirit Comics, and I still have those comics, somewhere, to this day.

When I started writing comics in 1969, my very first script for the series I’d created Detectives Inc.: All That’s Left is Anger, I had designed a title page that incorporated the words into the art. But I’m sure, even now, that it wasn’t Will who inspired the idea of working the title into the design of the page. I loved Jim Steranko’s Nick Fury Agent of SHIELD, and in many of those comics, Jim utilized that design, integrating the titles into the art.

Now, Jim was obviously well aware of Eisner at that time. Jim knows a lot more about the history of comics than I ever will.

Jim has never told me if he was inspired by Will’s many splendid and ingenious ways of starting off splash pages in The Spirit. I’ve never thought to ask him. But in writing this piece, all I know is, it’s a form of comics story-telling that I’d loved, and have often done in my work through-out the years. I’ve come to think of it as Eisner influenced by way of Steranko. That’s about as close to the way it was as I’ll ever be able to figure it.

In the 1970s, as Jim Warren printed The Spirit Magazine, I became much more aware of the character, and of Will’s work.

I can think of two instances where Will directly inspired something I was writing.

The first was in an adaptation for Marvel Comics of Wilkie Collins’s The Moonstone. I forget how long that damn book was, 600, 700 pages, something like that. I kept every chapter. I got every major sequence in there.

I worked like a sonofabitch on that book, proof for some that I was crazy, indeed.

There was a long section of the book where it dealt with several major characters, and what they were doing, over the course of a large number of pages. I needed to condense the material, yet try to find a way to hopefully retain the essence of it.

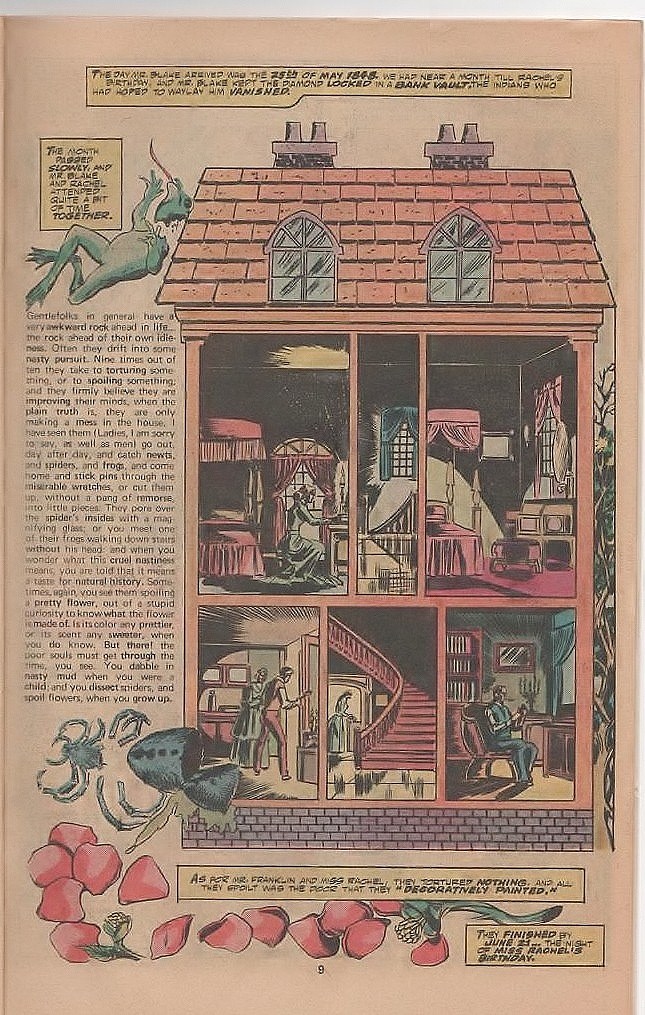

Will had done a P’Gell story about, I believe, a boarding house for girls where, if I recall correctly, murder occurs. I haven’t gone back to try to find these books, so I’m relying totally on memory. Whatever the exact storyline was, what I do recall vividly is that Will had done a page that showed the entire dormitory, and he cut away through the wall so that we could see into every room, see what each person who lived in that room was doing. [Editor’s note: the story is “School for Girls”, The Spirit Section for January 19, 1947.]

.jpg)

This was the exactly the approach I needed to show each one of the characters in The Moonstone. I used copy directly from the book, employed that specific design of the cutaway walls, this time showing inside a mansion, and managed to get a lot of pages of the book covered in a single, beautifully designed page. I would never have come up with the idea if I hadn’t seen what Will had done.

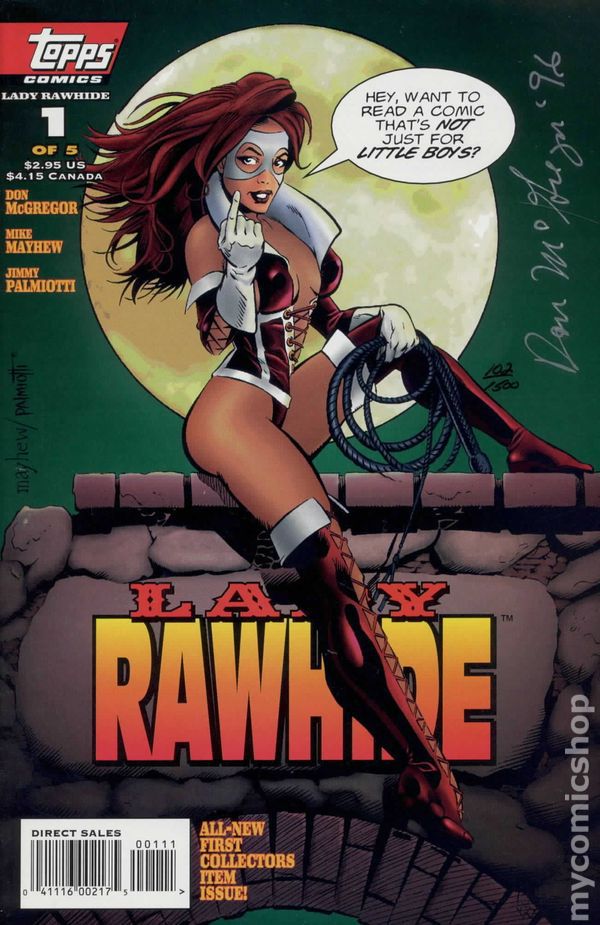

The second example, which I used twice, was for the first page of “Crimson Dawn: Final Transactions” inSabre #9. The splash page never really worked the way I’d hoped. It showed a beckoning Crimson, breaking the fourth wall, and talking directly to the reader, saying, “Hey, men! Wanna hear a story…that’s not for little boys.”

Will has a famous splash page with P’Gell that was definitely the major factor in the kind of approach I wanted to do.

I redid that idea years later, to better effect, with artist Mike Mayhew, in the cover for the first Lady Rawhidemini-series: “It Can’t Happen Here”. Apparently, it was a well-liked idea, since I discovered someone had sculptured the scene, with Lady Rawhide atop the wall, finger crooked, looking outward, while strolling around the tables at Thriller Con. I asked the sculptor where he’d gotten the idea. He said it just came to him. Uh huh. When I told him who I was, he wasn’t sure what to say. But he was inspired. He asked me if I’d like a sculpture of Lady Rawhide in that pose. I thought I might. I still have it to this day.

Whenever I really look at that seductive figure of Lady Rawhide, I think fondly of Will Eisner.

I’m not too much up on all that is going on in comics. I guess I've never had a compulsion to be trendy.

But I’m aware that there is some kind of debate going on about the publication of my series Sabre, and Will’s b

ook A Contract with God.

The debate, from what I understand of it, is which book is the first graphic novel. Or something like that.

Both books were apparently published about the same time.

I didn’t know a thing of what Will Eisner was doing at the time, or even about his book until much later. I was working in a loft on the Bowery, creating the characters that would be in Sabre. It was also a time of passionate discovery, of being in love with a beautiful woman, my wife now of 27 years, Marsha Childers, in what was, and is, for me the most incredible city in the world, Manhattan. It was a time period of creativity and joy. It took us fifteen minutes to walk one block. I couldn’t keep my hands off her. She couldn’t keep her hands off me. She was an unconventional woman, of beauty and compassion and talent and heart and sensuality.

I will savor those days to the end of my life.

The point here, for this piece on Will is, that with all this in my life, I didn’t have too much idea what else was going on in comics.

The debate seems to be over which was the first graphic novel.

Sabre was never a graphic novel. Not in my mind.

How could it be?

The one imperative, the one specific set in concrete, that I could not change, was the page count of the original book.

38 pages.

I had 38 pages to come back to an audience who had been reading my stories of the Black Panther and Killraven over a 2 to 3 year span, and convince them it was worth the journey.

In 38 pages you do not construct a novel, graphic or otherwise.

If there is one thing unique to Sabre, I suspect it is because it was a book aimed primarily at a marketplace that no one was positively sure existed: the stores that just sold comics. I do know that when I was in the hallways of the major comics companies, many of the people who made their living in comics did not believe that there were enough stores to support such an endeavor.

If Sabre proved anything, it was that there was a market place there.

Now, I don’t know this for sure, but I believe A Contract with God was sold in book stores, as well as comic stores. I have never read the book, but I’m sure it’s much longer than Sabre, and if the word “novel” applies, than maybe it should be used with Will’s book.

I am sure if there was a way Dean Mullaney could have figured to get Sabre into bookstores, he wouldn’t have jumped at the chance. I would certainly have encouraged him to do it.

Heavy Metal wanted to publish Sabre after seeing some of the pages. Maybe then it would have been seen in bookstores. I don’t know. But I had given my word to Dean Mullaney, and he had kept his word to me. Your word is your bond. He had paid everyone to do their work, the way he had promised. I made sure everyone had a higher page rate than they had at the big comics companies. I believe I took an advance of $300.00, to pay the rent. I wanted Dean to be able to afford to do the book. It would take two years before SABRE finally became print reality.

I’d have to wait two years to know if I was right, that there was an audience there, and hopefully find a reward then.

Will Eisner didn’t influence me in going my own way.

But he certainly went his.

He had a profound influence on so many of us, in the ways to tell a story in comics, how many diverse ways there might be. He opened many of us to the possibilities.

And he will always have that influence, whether directly, or through others he inspired.

Thank you, Will.

The Official Website of Don McGregor

The Official Website of Don McGregor