Two Stories About My Dad for Father's Day

Copyright © 2012 by Don McGregor

This is one of my earliest memories of my Dad.

I'm maybe five, maybe six years old.

The family is sitting at the dinner table. My Dad sits at the end of the table near the screened doorway, his back to it. My sister, Susan, and I sit on the sides facing each other. My Mom is at the other end of the table.

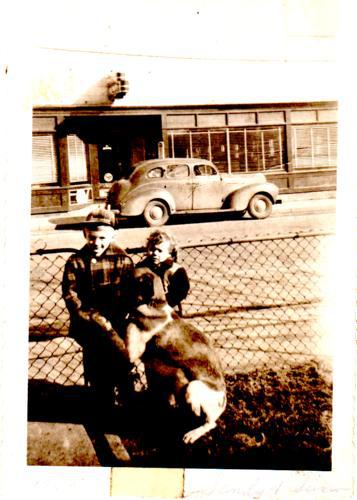

It is still light outside the screen door, and it is still warm. The doorway goes out onto a landing, three cement steps up. There is a railing made of piping, probably done by my Grandfather Doucette, who had a plumbing business. Our place was a side entrance behind his glassed engraved business front. A cement walkway comes up from the gate in the chain link fence that fences off our yard from Main Street. The grass grows around the stoop and continues to the backyard, where it mostly dies, into clumps poking out of dirt.

We are eating when the day turning into dusk is broken by a woman screaming.

The scream becomes louder as the woman runs into our yard, over the grass on the other side of the landing. A man is chasing her, and reaches her just as she reaches this spot beyond our door.

The man takes the woman down onto the ground. She is still screaming. It has only been seconds since we heard her before she became flesh and blood reality in our world.

My dad, who has had his back to the door, whirls about, pushes out the screen door, vaults over the pipe railing, lands on top of the guy on top of the woman, yanks him off, and has him in a Hammerlock which the guy cannot break.

He does this in less time than it takes me to write these words and for you to read them. I am five years old. My eyes are wide.

It is the first time I have seen my dad in action.

I realized, as I grew older, that I'd want to assess a situation, make sure what the right course of action was, make sure I should be involved, and then act.

Not my dad.

If something was going down, he took immediate action, and his philosophy was, get it done, get it done quickly, get it done without getting hurt, or with the least hurt to yourself, and let everything sort itself out afterwards.

Back when I was younger I saw him in action a number of times.

Back when I was younger I saw him in action a number of times.

Someday maybe I'll write about those times. But those are other stories. There's always another story.

Life is a series of stories, and when you put them together, and if you do it with care and insight, maybe it captures a little of that singular life.

But I will write one other story about my Dad.

When I got my first allowance of a dime, at five years old, I bought my first comic, a Hopalong Cassidy comic. I don't recall a time I couldn't read. I wanted to read the comics.

My dad came home and asked me what I'd done with my dime. I excitedly showed him my treasure. His eyes did not suggest I'd found the El Dorado.

The next week I got another dime. It must have been the week the next issue of Hoppy came out, and without hesitation, there went the dime, and when Dad came home, he asked me what I'd done with my dime.

Dad wasn't thrilled that I'd taken my entire allowance and spent it on another comic.

He said, "No son of mine is going to read comics." Which he never enforced, because I always had comics.

And when I was older, I'd joke with Dad: "So, what are you going to do now, Dad? I'm writing comics."

But now, back to 1951, where my Mom says something to me, like, "Comics aren't worth a dime."

This is how that statement translates in my five or six year old brain.

Well, if one comic isn't worth a dime, then certainly two comics must be a worth a dime.

And so while I perused the issues behind the candy counter, I smuggled one comic inside another, paid my dime, and had two comics.

Certainly no one could say that wasn't worth ten cents.

Even though my Mom is a worrier, this is a different time period. Even at 6, I get sent up to the store, to buy something for Mom and Dad. I take a lot of time, because I have to go behind the candy counter and go through the comics. And make my choice of two comics for one.

I am walking back home, past the huge Mill that the town had originally been built around. There is tall, wheat colored grass to my side, Main Street on the other side of me. I am reading one of the comics as I walk. Further down, toward where I live, trees will grow thickly, and the embankment will drop steeply down to the Mill River my Mom is always afraid I will drown in or drink from and poison myself. She is right to be worried about all these things.

I am engrossed in the comic as I walk.

I somehow manage to glimpse over the top of the comics.

My dad is heading up the sidewalk toward me!

I'm in six year old panic.

I'm not supposed to have comics, just whatever I was sent to get, and more to the point, where did I get the money for these comics?

Quickly, I side-toss the comics into the tall grass, my heart beating fast.

Did Dad see? I don't know.

Dad reaches me and asks me what took me so long. I don't know what I mumble in reply, but we start walking toward home.

I got away with it!

Dad didn't see.

He talks amiably to me all the way home.

Home! Home free!

We go through the gate in the chain link fence.

We walk up the cement walkway.

We climb the three steps.

< span style="font-size:14px;">I open the screen door.

And then Dad gently puts his hand on the screen door and pushed it closed, and looks down at me and says, with perfect timing, "Now let's go see what you threw into the grass back there!"

My mouth just drops open.

I can't believe it.

Dick Tracy was right. Crime does not pay!

Dad had waited, baited me, let me think I gotten away with it, talking nonchalantly to me until we made it to the house, and now I had to make the long walk back, a dead kid walking, knowing I had no excuses except Mom had told me comics weren't worth a dime.

And even at six, now caught, now faced with reality, I know that however I had convinced myself in my head of that, how in thought it seemed justified, now, with Dad, this was not going to fly.

.jpg) I think back on how exquisitely Dad did this.

I think back on how exquisitely Dad did this.

So, I'd never forget.

God, he's been gone too many years.

For years, I couldn't talk in depth about him without the emotion overwhelming me.

I still hear his voice.

I miss you, Dad.

I'll miss you until my last breath.

Don McGregor is the writer of Killraven, Black Panther, Nathaniel Dusk and a slew of other classic comic books. Order a copy of The Variable Syndrome and other comics from his website or his outstanding Detectives, Inc. at Amazon.

The Official Website of Don McGregor

The Official Website of Don McGregor